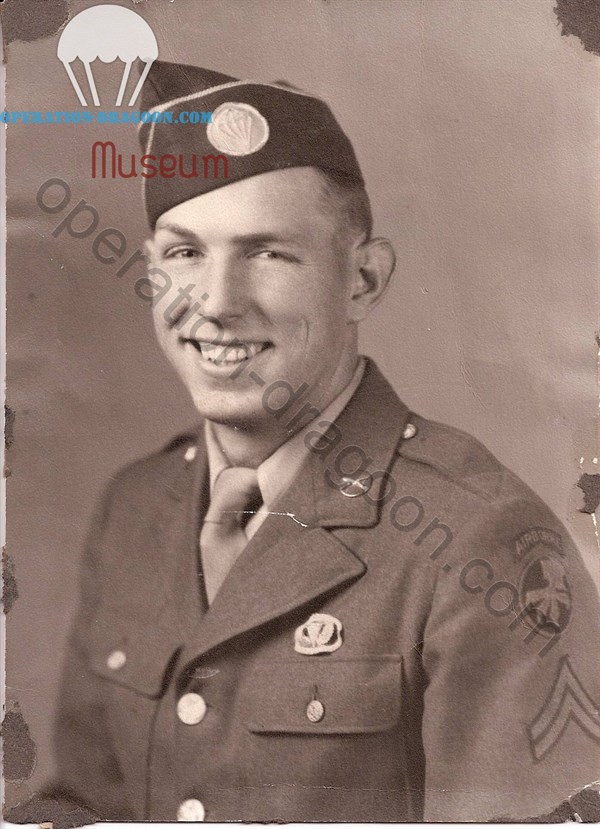

Hoyt KELLEY came back in Southern France in 2013, at this occasion we recommand the mayor of Les Arcs to award him as a honnorate member of the town. It was also for us the opportunity to drive him where he jumped and recording his war experience : « I was in the class of 1941 so just graduating from high school and not old enough to go in the army when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. I remember well the day that seventh of December as we were rehearsing for a pageant at the Stake Tabernacle in Logan, Utah. Someone came and told us that the Japs had bombed Pearl Harbor, and I

remember asking someone where Pearl Harbor was. I did not recognize the significance of that treacherous act at that time nor the effect it would have on my life and those in my family. The war had been going on in Europe for some time, but there was a strong sentiment in the U.S. about not sending our boys into war again on foreign soil and some of the most prominent Americans, Charles Lindbergh,

I remember my father telling me that the same feeling prevailed before the Spanish American War. That the people were violently opposed to the entry of the U.S. into that war, but through the sinking of the battleship Mainein Havana Cuba.

It was in my second year of college that I entered the service. I had taken a physical examination to get into the Marines about six months earlier but was turned down because I had a high count of albumin, and at one time the doctors told me that I would probably have Bright's disease.

It was early in 1943 that I went to Salt Lake City for a physical examination, after being served with a draft notice.

We were just the latest of those who had received "greetings from your fellow citizens" informing us that we were to report to Fort Douglas on this the first Monday in March. As the small train picked up additional boys at almost every little town along the line, we all sat in our own little group, not that we were total strangers, because this was the same train we had ridden to high school on for four years.

Five army trucks were waiting at the siding as we walked into the Salt Lake Train station. We piled off the train and climbed into the back of the trucks which had rows of benches built into the bed. A couple of army guys, corporals, made sure we were packed in tight by adding a fewmore bodies than the truck could reasonably hold and then we started our caravan for Fort Douglas. Our arrival at Fort Douglas was equally unceremonious. The trucks pulled up alongside a barracks, we unloaded and stood outside the truck until we were formed in the right number of men for each barracks and then marched by a Non-Com into the barracks where we would be housed until assigned to our respective camps.

Neither I decided to volunteer for the Army Paratroops, which was the only volunteer service in the Army. The Navy had a volunteer service for submarines, but you couldn't get into that if you were over 5'6" tall. TheMarines also had paratroopers but they limited by weight to 140 lbs.

Camp Taccoa was between Taccoa Georgia and Cornelia Georgia in the northern part of Georgia next to South Carolina. A beautiful, heavily wooded area, it is covered with southern pine trees and quite a variety of other trees. The camp held two regiments at one time. It was a red clay area with the needed number of barracks, a Catholic Church, a Protestant Church, and little else.

The first day in Camp Taccoa was as were most of the following days, testing days, to see if we would stay or get kicked out. Many were reassigned. No fuss was ever made we just did not see the soldier one day and knew he was gone. The first day

they lined us all up at the mock up tower. This tower was actually a box about four feet in width, height and length on top of a 40 foot pole. They had a cable angling down to the ground from the box. You had to climb the ladder, stand in the doorway (similar to a plane) and when they slapped you on the leg you jumped out coming down to the earth sliding down the cable. I was about tenth in line when a fellow went up the tower, was standing in the door and I guess someone accidentally touched him on the leg before they had the harness hooked up to his back. Anyway he jumped and fractured both legs. As he was lying moaning on the ground waiting for an ambulance to come, the Sergeant in charge, said to us. "Just stay in line. That only happens to about one in twenty of you guys". There were a couple of the fellows who asked for transfers rather than take a chance on the "mock-up tower". The food was minimal, the hours were long and the punishment was usually push-ups. We had to be able to do 100 push-ups to stay in the outfit, along with passing time tests on various items in the obstacle courses.

I had only been there a few days when the fellows came in the barracks and told methat the Catholic Father was out on the steps and wanted to seeme. Officers often sent someone into the barracks, rather than coming in themselves and having the whole barracks snap to attention. I went out, telling the Father that I wasn't a Catholic, despite myname being Kelley. I had trouble with this previously as they automatically put “C” on my dog tags. Father Guinette told me he knew I was a Mormon.

Camp Taccoa was a basic training camp. The trainingwas rough and it seemed the purpose was to get rid of anyone who could not make it. We were a combat outfit. We were informed that there would be no applications accepted for O.C.S. (Officers Candidate School), as we were to go overseas as a fighting unit. We ran for sixmiles every morning starting at six, and had the usual training of marching and gunnery range in addition to specialized training for jumping out of planes. They had mock up towers to jump from, and we had to practice jumping from heights of 12 feet, landing and rolling. Much of the paratroop training was still in the experimental stage.

We were the first regiment to jump with the Army helmets which weighed six pounds. Previous jumpers had used the air corps crash helmets. They had also used folding stock carbines, and we jumped with the M1 Garand Rifle. The first regiments were taught to jump with their feet apart so the shock would go equally to their hips, we were taught to jump with our feet together, because of the high number of fractures they had.

Of course one of the things we liked was our ten inch jump boots with our pants tucked in, and we wore the soft army hat, cocked to one side.

Toward the end of our basic training they selected about a dozen of us for Military Intelligence Training. I remember Captain Mitchell, who was an English Captain who had been brought over to teach our Military Intelligence School. He was really a nut, but smart.

There was no time for games, entertainment or anything else, we were dead tired. After a few weeks and dependent on our good behavior we were granted passes to go into town. Taccoa had a USO Club, but was a small town with little else to offer.

As Paratroopers we got the usual army pay of $50.00 amonth, an extra $50.00 jump pay and as I recall, I got another $46.00 for being a staff Sergeants. The officers got $100 for jump pay.

They got about $200 amonth regular pay, but had to pay for their own uniforms and a few things we didn't. By in large, I believe, every officer in our regiment who was a Captain or higher came from West Point. They were mostly ex-cavalry

officers.

From Camp Taccoa we went to Fort Benning, Ga. for jump school. Fort Benningwas one of the larger military camps in the U.S. and is at Columbus, Georgia. While the camp was much larger and had better facilities for the troops stationed there it was a terrible training camp for Paratroopers.

It was nothing but sand, and marching and running was tedious. The weather was hot and humid. The food was terrible. Usually it consisted of a boiled potato, salt pork and grits. They said it was field rations and that the purpose was to get us used to eating less food.

They had a 325 foot jump tower at the base, and part of our training was the same as at Taccoa, only with better equipment. We had to complete five regular jumps from planes to get our wings. The jump field was a large pasture area, bordering the Chattahoochee River.

I think the first two jumps Imade I was swinging in the wind and landed almost flat on my back, and I didn't think I would ever jump again. Since we jumped with helmets, they were probably the greatest hazard as they would come whistling down, if loosed from someone's head. The third jump, I landed very easy and never had a fear of jumping after that time, later

making upwards to four jumps in one day. I attended Military Intelligence School at Benning while the Regiment was being relocated at Camp McCall in North Carolina. They would take us out in a plane and drop us over Alabama, where we would have to find our location and set up road blocks etc. They would fly over with a small plane a short time later and

bomb us with flour sacks. Usually we landed in peanut farms, where you would sink half way to your knees in the soft soil. The planes we used were C43s and C57s as I recall, the same plane was the DC-3 transport plane. The 57s were old even then and sometimes theywould take a long time in gaining enough altitude to jump. Our jumps at Benning were made from 1300 feet, later in combat we jumped at 400 feet, which didn't give much time for an emergency chute, but left you in the air for a shorter time. In Southern France we didn't use emergency chutes at all (those of us who went in early in the morning) because

we didn't think we would have time to use them, and with our weight of equipment we felt the risk warranted not using them. We spent some time at Camp McCall, which was near Fort Bragg North Carolina.

I had two men who were in my S-2 (Military Intelligence Group) killed at McCall. One was impaled on top of a tree when he came down, the other hooked his rip cord through his chest harness and when he jumped it pulled the rip cord through chest.

Without any notice we received orders to get on trucks that would transport us to Newport News, Virginia for transport over-seas. We had much of our training, hacking our way through growth with machetes, andmost of us thought that we would be going to the Pacific, but that was not to be the case. The Newport News Camp was a holding place until ships arrived for transport, and we stayed there about two weeks.

The next day we loaded on the ship for overseas.

We departed the harbor at Newport News, bound for Naples, Italy. I had a strange feeling that this was not only going to bemy first trip aboard an ocean going vessel, but that the ship I was boarding was not the usual one used for Army transport. The ship was the S.S. Santa Rosa, and had been one of the Grace Luxury Liners that toured South America.

The 517th Airborne Combat Team sailed from Newport News on May the 17th of

1943. It was always easy to remember because we were the 517 sailing on 5/17. In addition to the 2,300 paratroopers there were 200 WAAC’s (Women's Army Auxiliary Corps). Our ship was one of fourteen in the convoy, which included three transport ships loaded with various units of the army, and the rest of the ships, which were freighters and destroyers or other navy support craft. All banded together for mutual protection from the German U Boats (submarines). Our route

covered a lot of the Atlantic Ocean as we zigzagged across taking fourteen days tomake a journey that should have lasted about seven days.

The first land we saw was Gibraltar and we passed quite close to it as it was controlled by the British. The next day we came into port at Casa Blanca in Morocco, and about half of the WAAC's debarked there. I don't think there

was any fighting going on at that time in Africa, but it was being used as a base for air corps support for the army in Italy and there were several rest camps there for injured and mentally disturbed soldiers.

Naples Harbor, Italy (1944)

The Voyage Over -20- We next had a brief stop at Palermo, Sicily, which had been much in the news and was of great importance to us as Para-troopers. During the fighting to control Sicily they had flown in Paratroopers (whom I believe were from the 101st Regiment), but the navy and the air corps couldn't get their act together and they shot down the planes. We lost many Paratroopers in that fiasco, although it was not widely known in the U.S. (where they were trying to keep up the spirits of the citizens so they would buy war bonds and support the brave boys in the war). After only a couple of hours at Palermo in

Sicily we moved up the coast past Salerno,where there had been recent fighting and into Naples Harbor.

The portion of Italy south of Rome was at that time pretty much out of the war. The Germans were fighting a delaying action, mostly with Polish, Czechoslovakian, and Yugoslavian soldiers. These soldiers were very reluctant warriors. If they retreated the Germans would kill them and they usually opted, if given a chance, to surrender to us. Where there were large groups

of Germans, the situation was very different.

Major Boyle had ordered everyone to dig a

fox hole, but eventually the Major, like all of us, found the bales of straw more comfortable than a hole in the ground.

Considering the weather in Italy, our outfitwore fatigue uniforms instead of the woolen uniforms worn bymany solders including the Germans.

After another day we received orders tomove to Orbetello and join the 36thDivision on the line where they had been fighting for two days, not because of the town, but because of a certain big hill behind the town where the Germans had an observation post that commanded the country within ten miles.

From that time on we were ordered by the 36th to take hill after hill as the war arena moved up Italy. We were inland a few miles, while the 442nd, particularly the 100 Battalion of Nisei (Japanese Hawaiians) were attached to the 100th Division who used them as their leading force along the coast.

I think history will show that the 442nd and the 517th were used to excess by the divisions to which they were attached.

We were sent in to take a series of hills between the ocean and the central area of Italy. The front was moving north rather fast at that time, and I don’t think anyone was sure where the enemy was. Our first real encounter with the enemywas taking small hills that led to higher hills. There was a valley over the first hill and the enemy was down in the valley trying to escape over the next range of hills. Those hills, I would guess, were about 1,500 to 2,000 feet in elevation and about ten miles

inland from the ocean. We could see people down in the valley and there was a lot of gun fire on both sides. We had 81mm mortars and 60mm mortars as our heaviestweapons, and our 75mmhowitzers back somewhere down the hill with the artillery battalion that was part of our combat team. There were quite a few trees down in the valley and some orchards had been planted on the opposite slopes.

Several of our men were killed in this skirmish, I think all by small arms fire. Theywere put

in mattress bags and loaded on a flat bed truck and taken back down the hill, without ceremony.

Eventually after about four hours the firing ceased, and all was quiet down in the valley. I remember

a German coming up the hill waving a white flag but someone shot himin the forehead. They said he

had emptied his gun at us before raising the white flag, so they killed him.

I can say now, without question it was my good fortune to be brought back from the front lines to Frascati, Italy to prepare for the jump into Southern France. At that time it was rumored we might jump into Yugoslavia, but I think we always knew it would be France. I came back along with another non-com and three officers who were to get the camp set up. I presume that the area we were to camp in had been determined earlier or by some higher command. We first stopped in Rome for instructions from the command there and the officers, thinking that the rest of the outfit would not follow us for two or three days, picked up some women in Rome and left myself and the other non-com at the site to get it set up forthe combat team when they arrived.

I remember the towns in Italy and France, where we would be the first troops to enter, and the people would welcome us as

conquering heroes, with bells in their churches ringing and line the roadways with wine for us.

I probably worked harder than most of the men as I was in charge of Military Intelligence and Training Operations for the Battalion, and we were the ones who planned much of the jump in Southern France. We knew about the jump a few weeks before the actual date, while most of the men didn't know about it until we were in the plane headed for France. Unfortunately as we were to later find out the Germans knew about it long before then. In fact, a few days before the jump in Southern France "Axis Sally" who was the German propaganda star, "welcomed the men of the 517th Parachute Infantry to France and said they already had our graves dug.

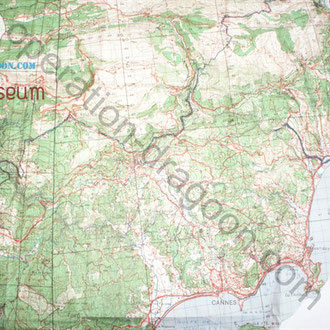

The plan for the invasion of Southern France was code-named Underlord. It involved a fleet of Navy Ships making a bombing raid on the beach area of Toulon, France the day before the actual landing, in the hope that the Germans would divert some of their army down there to stop the invasion. Our Combat Team was to jump in the area of Draguignan.

(where the road from Toulon joins the road from Nice and Cannes and then goes north into the middle of France). The purpose of our jump was to hold this area from Les Arcs to Le Muy, where the three roads joined, stopping any troops from coming in from Toulon or reinforcements being brought in from the main area of France. General Jake Dever was in charge of the Seventh Army which was our group going into France. We were to jump in early morning of the day the infantry troops hit "Red Beach" an area near Cannes, south of Nice. On the very early morning of the 15th of August we loaded into planes at the Ciampino airport about nine miles south east of Rome for the jump into Southern France. The planes had been instructed to

fly over the Point of Antibes, then three minutes due-west and turn on the light, which was our jump signal. Our planes were all C-3 Transport planes, which were to become an important plane in civil air travel for years in the U. S. It was only intended that we would get a chance for one pass at the drop zone, so there was just twelve of us to a plane. We were to jump at 300 - 340 feet.

A height determined to give the enemy little time to shoot us in the air, and barely enough time for the chutes to open. Since there was no time for an emergency chute we discarded them, and we did not carry gas masks.

I jumped with two pounds of TNT, a pound strapped to each ankle. Tetrol caps for igniting the TNT in my groin where there was the least chance of pressure igniting them. If we could not hold the area we were to demolish bridges, railroads and communications. I also had two bandoleers of rifle ammunition, my M-l (Garand Rifle) my switch-blade knife in a zippered pocket for cutting the shroud lines in case I landed in a tree or high tension line, and a pack on my back which contained D rations (which were a bitter chocolate bar), which I could exist on for three days until we had some food. Included was a small waterproof bag that contained silk maps of the area a tube of morphine and some bandage & tape. I still have the maps

but I don't remember at this time anything else we carried. We were required to leave all identification behind other than our dog tags, which merely gave our last name, service number, blood type and religion. We boarded the transport planes at an airport near Rome. We numbered about two thousand paratroopers all members of the 517th Parachute Infantry Team, which included infantry, a company of engineers and a battalion of artillery, the 509 battalion (an independent battalion which had seen action in Sicily), and an antitank battalion of the 442 (Japanese) Regiment coming in by glider the next day.

I went in ahead of the other troops with the Military Intelligence Unit, to mark the drop zone where we hoped to land the rest of the troops. Fortunately the plane we were riding in dropped us some six miles from our drop zone. We had to hike all morning to get to the original landing site (losing half of our men on the way). One of the reasons our casualties should have been much higher (as it was, we only suffered 20% casualties) was that the Germans had completely mined the intended drop zone, which was a large bare field where we had originally intended to land. Had any of our men actually landed in that field, they would have never survived.

The pilots of the transports that took us in were pretty poorly trained. Our plane was France to cross the Point of Antibes and fly directly west for three minutes before giving us the green light to jump. I do not know what the Pilot thought was the Point of Antibes but obviously he was a long way off.

I hit a stone fence in landing and cracked a hip bone. However, many of our men landed in the river, high tension wires and other hazards. One of the troubles was there was a low fog about twenty feet thick covering the ground, and many men thinking they were landing in water, prematurely slipped out of their harness high above the ground. This increased the casualties.

At first when I landed it seemed very quiet after the noise of the plane. We had taken off our reserve chutes and gas masks so we could carrymore ammunition and in my case, a back pack with a few D Rations (which were hard unsweetened chocolate bars). We knew we would have to live off the land until some supplies could be flown into us, but for the present, bullets were more important than food.

I came upon the little town of Les Arcs early in the morning, and as I got closer and the fog lifted it seemed almost a fairy tale place, with a farmer clanging his milk cans and the usual noise of early morning in a small farm community. I had two other members of my squad with me and the first sound that startled us was two Germans coming up the road on motorcycles. We shot and killed the Germans from the hill, and then moved into the town as more of our men joined us. When we got into the town, two of our Paratroopers were found in the church, shot dead with their hands tied behind them. The old French caretaker said the Germans did it, telling us that the Germans called us "Butchers with Big Pockets". I suspect this was reference to the jump suits we wore that had lots of pockets for all the things we carried and the pocket near our throat where we kept our switch blades in case we landed in a tree or somewhere where it was necessary for us to cut the lines from our parachutes.

Of course being as how we were behind the German lines they realized that we could not take prisoners, so there was never any love between the Germans and the paratroops. We knew if we were captured we would be killed, and I do not know of any of our men who survived capture, although I know of several who were captured. I mention these things to de-glamorize war. It is not like it is in the movies. There are no heroes, there are only survivors, dead soldiers and in some cases, the surviving

dead - but no heroes.

It was easy to hide up in the hills if one wanted too, so many of the officers who were to take over often did not show up until the area was secured. By about noon there were thirtyfive to forty paratroopers in Les Arcs, and so I and a member of B company, named Jim, left to go across the valley to the hills where most of our regiment was supposed to be, and try to establish contact with them. We needed to make sure the road, rail road track and telephone wires were not still intact. As we left the town and walked down through the vineyards and small farm plots, we were about two miles from the town when we

spotted about one hundred and fifty soldiers walking up the rail road tracks. Jim started to wave at them. They stopped and immediately started firing at us. It was then that we realized they were German troops and not our boys. I heard Jim moan as they shot him and I dived into the vineyard which had small plants and furrows about a foot deep. The Germans flanked part of their men into the field and started firing down the rows while the other continued firing from the rail road tracks. I could hear the bullets hitting me but I didn't feel any pain. I remember it was August 15th and my mother’s birthday was August 16th, and that was all I thought about. I thought how terrible that she would never be able to celebrate her birthday again without remembering that I had been killed the day before. I remember praying that they would find my body that day so that they would not send word to my mother that I had been killed on her birthday. I did a lot of praying in those days, but it probably came so natural I don't remember much else. I was laying on my gun, and would not have fired it even if I could as that would only have brought their fire directly down uponme. I could hear Jim gurgling like he was trying to breath with his throat full of blood.

All of a sudden the firing ceased and after a few minutes I looked up and saw the Germans marching very quickly down the railroad. I think something must have startled them, but on the other hand they had no reason to think they had not killed us as we were both standing straight up when they started firing. I waited until they were about a half mile down the road and crawled over to Jim. It looked like he had been shot in the mouth with the bullet coming out the back of his neck. I did not try to

go back to the city because that was the way the German's were going. I ran for the mountains, trying to keep low along the hedge rows, and down some small rivers that drained the valley. One particular area was lined with dead soldiers from my outfit, but I did not recognize them as they were from another battalion. I just remember they all seemed shot through the head, bees were going in and out the holes in their heads. I think they probably were killed by the Germans after they were taken prisoners, or the Germans were extremely good shots. I do not know. I think there were seven of them.

I had probably been running for miles and hours when I reached the mountains on the other side of the valley. There I found most of my regiment. They had set up road blocks and effectively stopped German reinforcements from getting to Red Beach fromToulon. BOYLE group at Les Arcs, after having engaged the Germans company who shot at Jim and I, successfully held that area, stopping any reinforcements from coming in from the Lyons France area.

When I got to the other side of the valley, one of the troopers asked me if I planned to fire my gun. I didn't know why until I looked at it. There was a hole where a bullet had completely gone through the barrel and another bullet had gone through the stock of the gun. I also had four holes in my back pack, which was only holding on by one strap as the other had been shot away. I did not have a single nick from a bullet although as I have previously said I was laying on my gun in the

vineyard during the shooting. The Captain asked me if he could have the gun as a souvenir and I gave it to him happily, finding another gun to use. I presume if I had tried to fire the gun it would have exploded. I was so scared (I guess that is the onlyword for it) and so completely exhausted that I had never thought of checking the gun, assuming I would use it anytime it was necessary. I remember one of the men on the hill, a felon who had been released from prison when he volunteered for the Army was performing a laryngectomy on one of the troopers who was shot through the throat. He cut a hole in the man’s windpipe and after cutting the top of his fountain pen, inserted it in the man’s throat saving his life. It was a couple of days later before they were able to set up a field hospital, but the man survived and there was a newspaper article written about the incident. [There was also a newspaper article written, about myself andmy gun that day, and published in a newspaper inWaco,

Texas. I used to have a copy which was sent to me by Doug Bertling's parents, but it has gone the way of the few souvenirs I had.

Two days after our jump a plane came in low and dropped two supply chutes. We risked our lives to go out into the open field to recover them, and when we got them back to the hill, we found that they contained just two things, copies of the "Stars and Stripes" newspaper from Rome, and cartons of cigarettes. To rub salt into our wounds, the front page article honored the brave pilots who flew us into France, quoting one Captain who said "It was just a milk run, we flew over and dropped the paratroops and came back." We all wanted to apply for a few days pass in Rome to look up that Captain.

From that point on I believe we walked overmost of the French Riviera, throughwell known cities such as Grasse, Cannes and Nice, and through hundreds of others, finally ending up for a few weeks on the mountains above Sospel at Piera Cava (a ski resort), and generally along theMaginot line which ran through Sospel. We set an army record of being on the front line for over 100 days without relief. To the right of us were troops which were English and Canadian. (First Special Service Force) But, we had no troops to relieve us. Our artillery support came from ships off of Nice, and they were very accurate against targets around Menton and Sospel. We had high

casualties in this area, because of a determined German force. Many of the shells that came in exploded in the trees, creating what we called “tree bursts,”which had the effect of large grenades (resulting in missiles that injured and killed those below).

We soon learned to live in fox holes and not slit trenches.

At that time and throughout the remainder of the war, I was the S-2 sergeant. Our Headquarters battalion was made up of a commander Col. William BOYLE,1 Major BOLBIE (S-1 Adjutant (or Asst. Commander) (S-1) Captain Bill YOUNG (S-3 - operations and training), and the S-4 who was in charge of supplies, kitchen etc. The S-2 (military intelligence) did not call for an officer, so I held that position, and doubled as the S-3 Sergeant for training purposes when we were not in combat. It was my job to run the patrols, and we would send out day and night patrols.

It was important that we knew where they were, and what reinforcements, ammunition etc. was getting to them.

We directed the fire from our 4.2 mortars on the area the next day and I thought the whole world was going up in flames.

They were effective as were the 4.2 mortars against personnel, but relatively ineffective against armor. We did get our men into Nice occasionally, usually for passes of one or two days. Since we were there from August until December, the weather in the mountains was cold, but at Nice just an hour away’ theywere swimming in theMediterranean. Nice was a very pretty town with people that were quite friendly, probably because it was once part of Italy, and there was still much of that influence there. Also, Nice was a great vacation area, so the people had an affection for tourists.

The hills I refer to are theMaritime Alps.They are extremely steep, and the army that controls the heights can wreak a terrible toll on an attacking army as we unfortunately found out. The roads zigzag back and forth climbing the hills, and with the German artillery accuracy, we had some very interesting trips.

As I mentioned before we set a record of being on the line longer than any other unit of the army, in Southern France or any other place for that matter. We were finally relieved about the first week of December, loaded on trucks, occasionally on trains, and moved north. The Allies had landed in Normandy in May we had jumped in Southern France in August, and it now seemed that the German Army was in full retreat on all fronts. We finally ended up in Soisson, France, which was aWorldWar I battlefield. We were housed in barracks there and a detachment went to England to arrange for a supply of Turkeys for our Christmas celebration.

All of this changed suddenly, around the middle of December. Things were about to get much worse. After setting a combat record of 94 consecutive days on the front line in Southern France we were relieved by new troops and with little warning we loaded the regiment in trucks . I rode in the back seat of Colonel Boyle’s command car, and thought I had a wonderful spot to sight-see France.

On December 23rd, two days before Christmas, General Von Ronstadt’s army struck with the most violent offensive of the war. It now seems almost suicidal, but it was well planned and caught the Allies completely off guard. The German Armored Divisions came through our lines, circled several of our divisions and they were moving with speed as their only hope of success lay in capturing enough fuel to keep their tank rolling.

Within about three days in the cold, sleeping out in the open with at best an army blanket for warmth, and no food we were reduced to the level of animals. We took overshoes and overcoats from the dead Germans and Americans and searched their pockets and backpacks for food. Some of the Germans had items that looked like Graham

Crackers, but they tasted like sawdust, which is probably what they were made from. I possessed an army blanket that I had brought from Soissons.

The main thrust of the Germans had been in the vicinity of Manhay and since they were already there we were diverted into the town of Soy.

We set up a perimeter defense around the town, and tried to get with theArmored troops to determine what the situation was.

After several days, the Germans were forced out of the town and our troops returned. The First Battalion, of which I was the Staff Sergeant, was given a command to rescue a platoon of the armored division surrounded by the Germans in a town called Hotton. An American Infantry Division, (I think the 79th) fresh from the states had tried to get them out but had been annihilated in the attempt.

When the Germans retreated from Stavelot we followed them to Aachen, Germany. The citizens of Aachen were out cleaning and stacking bricks from the bombed buildings. At Aachen we were attached to the 82nd Airborne Division, and fought with them through the Ziegfried Line, which was a series of pill box type fortifications and tank traps that made fighting very difficult. The Artillery and tanks had little effect on the pill boxes.

Our last serious battles were fought in the area called the Hurtgen Forest. While we went

through forests, the cities including Hurtgen were complete rubble. There had been somuch tank and artillery fire that nothing was standing above about 4 feet high.

.” Out battalion was given the mission of stopping the Germans from destroying a dam on the Oder River, which if blown would inundate a large area of the front we were in. We lost a lot of our second battalion that night as they got into a mine field.

Melvin

BIDDLE, who won the Congressional Medal of Honor, was with the 2nd Battalion. After we came back from the lines I had the job, along with a few others, of writing him up for the CongressionalMedal of Honor, which he later received. Being the Operations Sergeant for the Battalion, I always had maps for our operations. They needed my maps and descriptions of the terrain.

After following the retreating Germans through Aachen toward Cologne, we were pulled back to an airfield at Amiens, France. There, we were alerted to jump three times but in each case Patton’s 3rd Army had passed the drop zone before we could get there. While there, I remember a sign posted on the Air Corps notice board, that effective that date every member of their command could wear another oak leaf cluster to their bronze star for gallant action fighting the enemy. Medals were a joke, as far as we were concerned.

The only medals that made sense to us were the Purple Heart and the Congressional Medal of Honor. All other medals could be won by sitting at a desk or other jobs far away from the front lines.

On May 7th I was sent to Allied Headquarters on Victor Hugo Blvd. In Paris, near the Arc De Triumph, to obtain maps so we could plan drop zones in Norway. As we were entering Paris, there was much excitement, and the noise grew louder as we got closer to the center of the city.

There were Russian soldiers marching and singing the International, French soldiersmarching and singing theMarseillaise, and Polish, English and Americans, and probably all the nationalities of Europe and much of the world. We were at the Place de la Concorde, and not ten feet in front of me was a man taller by a foot than us all. He was standing on a monument deck and trying to speak to the people. I realized it was General Charles De Gaulle. I didn’t know a word he said and I doubt if any people could hear him above the tumult of the crowd.

After a few days in Paris helping the French to celebrate Victory in Europe Day, we returned to our troops in Amiens and shortly thereafter we were relocated to Joigny, about fiftymiles south east of Paris.

We left the historic city of Amiens with its world renowned cathedral to go to an even more picturesque French city : Joigny.

.

The days in Joigny were wonderful compared to the Belgian Bulge. It was while at Joigny I had the job of helping to write up Melvin Biddle for the CongressionalMedal of Honor

Since the 517th had fought in two theaters of war, African-Mediterranean and the European, and you got points for discharge for each medal, wound, campaign ribbon, etc. most of us had enough points to warrant a trip home to the states to cadre a new outfit for the Pacific, or we could choose to volunteer for occupational duty in Germany.

Two days later they announced that the 517th had been reassigned to the 13th Airborne, and that we would be leaving for

Le Havre and shipping out through the English Channel for home.

Since the 517th was assigned to the 13th airborne, and they had arrived in Europe just as the war ended, we were given

preferred treatment and left Le Havre on a Victory Transport two days before the rest of the Division sailed. The rest of the Division sailed on the Queen Elizabeth, and passed us about three days later as we were wallowing in heavy seas.

They got to Camp Shanks, up the Hudson River about three days before we did – So much forseniority. But the good news was, the first atom bomb was dropped during the second day of the voyage after we left Le Havre, so by the time we got to the United States both wars were over, and we knew we would be sent home for demobilization.

Getting out of the Army and returning to Civilian Life was something we were not prepared for. At the time of

discharge they asked me what my experience in the service would qualify me for in Civilian Life. I told them probably a

bouncer in a night club.

When I got out of Camp Shanks, I immediately headed home, which took about three full 24-hour days by train. Arriving in Providence, I told myMother that I wanted to visit Dorisse in Los Angeles, where she was staying with her friend, Ruth Ellen Athay and family. My Mother was a little unhappy because the city of Providence had planned on a ceremony to honor the returning veterans. I have carefully avoided such ceremonies most of my life, and I went to LosAngeles.

Dorisse and I knew each other by letter, probably better than most young people do. We had some things in common: religion, a love of music and the arts..."

Hoyt was the recipient of a Bronze Star, three Purple Hearts, as well as a Special Presidential Citation that was awarded to his unit for heroism in the Bulge.

In August of 2013 when he returned to southern France at the invitation of the French government and was awarded the French Legion d' Honor, the highest military award given to non-Frenchmen. Since returning from France, he has spoken throughout the state of Utah about World War II, the gratitude of the French people and the contributions of the Greatest Generation. Hoyt KELLEY died on the 17th of july 2014 aged 91.

all right reserved, courtezy of Hoyt KELLEY and his children.